The Austrian psychologist and Holocaust survivor, Victor Frankl, once wrote, "Man does not simply exist, but always decides what his existence will be, what he will become the next moment. By the same token, every human being has the freedom to change at every instant."

“I am only one, but still I am one.

I cannot do everything, but still I can do something.

And because I cannot do everything,

I will not refuse to do the something I can do.”

Edward Everett Hale

Friday, 27 December 2024

The Power to Change

Friday, 20 December 2024

Equal Justice for All

I found this week's quotation, by the 20th century American political philosopher, John Rawls, somewhat opaque. It read, "Every person possesses an inviolability founded on justice, that even the welfare of society as a whole cannot override."

Friday, 13 December 2024

Wisdom of the Tao

This week's quote is allegedly by Lao Tse: "In the pursuit of knowledge, something is added every day. During the practice in the Tao, something is dropped every day."

Friday, 6 December 2024

Striving for Objectivity

It is very easy to fall into judgement when we read in the news of the words or actions of someone we do not agree with. It is much harder to appreciate that they, too, have their story. They, too, have come to believe what they do through the sum of their own life's experiences.

So I was interested to read Peter Singer's words this morning. He wrote, "By accepting that moral judgements must be made from a universal standpoint, I accept that my own interests do not count more than anyone else's interests, simply because they are mine."

I believe that that kind of objectivity is something we should all strive for, even though it's so hard. It involves the practice of empathic compassion, the ability to put yourself in the other person's shoes without judgement in an attempt to understand where they are coming from. It means walking alongside them in the darkness and making the hard decision not to flip on the light, to interfere.

We live in a very adversarial world - if you're not for us, you're against us. And the go-to response when we don't agree with someone else seems to be violence, whether it is verbal, physical or psychological. I wonder how different things would be, if we (whether as individuals and governments and pressure groups) all took time out to try to see whatever the issue is from the other person's point of view?

You may think I'm wrong - that there are certain things which are always wrong - war, exploitation of the planet, violence towards other living beings. And I would have to say I agree. Yet I still believe that returning violence with violence, trying to bludgeon the other viewpoint into submission, does not - cannot - lead to peace and restoration in the long run. We need to find another way.

Friday, 29 November 2024

Defend Your Right to Think

The 4th century Greek Neoplatonist philosopher and astronomer, Hypatia of Alexandria, once wrote, "Defend your right to think. Thinking and being wrong is better than not thinking."

Friday, 22 November 2024

Our Senses as Touchstones of Reality

The Italian Renaissance polymath, Leonardo da Vinci, once wrote, "The spiritual things which have not passed through the senses are vain, and they produce no truth except harmful ones."

Friday, 15 November 2024

Wanting What We Don't Have

I believe that this week's quote, by 17th century French writer and moralist, Francois de la Rochefoucauld, is advice which, if taken by the world's governments, by all of us, would transform the world for the better. It reads, "Before you ardently desire something, you should check the happiness of the one who already owns it."

Friday, 8 November 2024

Holding on to our Dreams

There's a wonderful post doing the rounds on Facebook at present, in the wake of the US election result, written by environmentalist, Chris Packham. It reads, "Things have just got a lot more difficult. Here's what I think. I had no control over what just happened. None. But I do have control over how I will react to it. And I am not going to give up on the beautiful and the good, the grip on my dreams just got tighter."

Friday, 1 November 2024

The Importance of Self-Love

When I read this week's quotation, by the 13th / 14th century German theologian and mystic, Meister Eckhart, I had a strong reaction to it. It reads, "All the love in this world is built on self-love."

Friday, 25 October 2024

The Benefits of Meditation

I'm away from home this week and had forgotten to bring this week's postcard with me. So I appealed to my friend, with whom I am staying, for a suitable quote, and she came up with this: "Buddha was asked, "What have you gained from meditation?" He replied, "Nothing. However," Buddha said, "let me tell you what I have lost: Anxiety, Anger, Depression, Insecurity, Fear of old age and death."

Friday, 18 October 2024

Nothing is Certain

The early 20th century German author and painter, Ringelnatz, once wrote, "What is certain is that nothing is certain. Not even that."

Friday, 11 October 2024

Using Our Own Reason

The 18th century German philosopher, Immanuel Kant, once wrote, "Enlightenment is man's release from his self-incurred tutelage. Tutelage is the inability to make use of his understanding without direction from another." And it continues, "Have courage to use your own reason - that is the motto of enlightenment."

Friday, 4 October 2024

Between a Rock and a Hard Place

I came across a beautiful short poem by John Roedel in my Facebook feed this morning:

"Between

a rock

and

a hard place,

let

me be water,

let

me be water,

let

me be water."

Friday, 27 September 2024

Coming to Rest in God

This week's quote is by the 20th century German Existentialist philosopher, Peter Wust, whose works have never been translated into English. According to my Google German to English translator, it reads, "Man is the eternal seeker of happiness, the tireless seeker of truth, the seeker of God who never comes to rest."

Friday, 20 September 2024

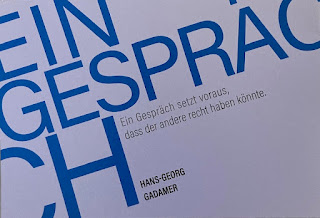

Respectful Dialogue

The 20th century German philosopher Hans-Georg Gadamer once wrote, "A conversation presupposes that the other person could be right."

Friday, 13 September 2024

Compassion: A Complex Process

This week's quote, by American philosopher, Martha Nussbaum, sums up beautifully the complex process which is compassion. She writes, "In order to feel compassion, you have to have a fairly complex sequence of thoughts: that another being is suffering, that this suffering is bad, that it would be good if it were alleviated."

Friday, 6 September 2024

The Start of Everything

The Buddha once wrote, "We are what we think. All that we are arises with our thoughts. With our thoughts, we make the world."

Friday, 30 August 2024

What is Tolerance?

The French Enlightenment writer and philosopher, Voltaire, famously asked, "What is tolerance? It is the consequence of humanity. We are all formed of frailty and error; let us pardon reciprocally each other's folly."

Friday, 23 August 2024

The Path to Contentment

This week's quote, by Roman emperor and Stoic philosopher, Marcus Aurelius, really speaks to my condition, as the Quakers say. It reads, "Think of what you have, rather than of what you lack! Of the things you have, select the best, and then reflect how eagerly you would have sought them if you did not have them."

Friday, 16 August 2024

Mary - an Extraordinary Mother

Mary, the mother of Jesus, is perhaps the most enigmatic of all mothers. Her story is simply told. According to the Gospel accounts, she was a young Jewish girl, betrothed to an older man, Joseph. She received an angelic visitation informing her that she was to be the mother of the saviour of the world, whose father would be God. The first thing about her that takes my breath away is her great faith - instead of having hysterics on the spot, which I think would have been quite justified in the circumstances, she accepts her fate: "Here am I, the servant of the Lord; let it be with me according to your word."

I have often wondered what it must have been like for her, bearing and raising such an extraordinary person. Even if we don't believe that Jesus was the divinely-begotten son of God, which most Unitarians don't, he was still very far from an ordinary man.

Mary has complete faith in him and continues to follow him, wherever he goes. She is there at the foot of the cross when he is crucified at the end of his ministry. And according to the Gospel of John, one of his last thoughts is care for her, when he hands her over to "the disciple whom he loved." In the Book of Acts, she is mentioned as being one of those in an upper room with some of the apostles, devoting herself to prayer.

And then she disappears from Biblical accounts. Yet she went on to become one of the most venerated figures in Christianity, not to mention Islam. Later Church traditions argue that not only was she a virgin when she conceived Jesus, but remained one for the rest of her life. Some go even further and state that she was born free of original sin, so that she could be a suitable vessel for the carrying of the son of God. Catholics in particular reverence her as the Blessed Virgin Mary, and she is often prayed to, to intercede on behalf of humankind.

But it is as a mother, an ordinary human mother, that she moves me. She brought him up, took care of him, taught him the best she knew, did her best to give him a good start in the world. Then, as all parents must, let him grow into adulthood. I know that 2000 long years separate us from Mary, but I believe that parenting has not changed. Her concerns must have been much the same as ours. I wonder with what mixture of pride and stomach-knotting fear she watched her son embark on his public ministry? In spite of the message from the Angel Gabriel, at the beginning of it all, it must have taken an awful lot of faith to stand by and let him get on with it, knowing the dangers he would face, and feeling powerless to do anything about it.

I believe that mothering, that parenting, of whatever kind, is the most important job in the world. All of us need somebody we can depend on to love us unconditionally. As Dave Tomlinson writes in How to Be a Bad Christian, "The heart of Christ's message was the love of God. He brought to ordinary people - downtrodden by ruthless rulers - the sense of their belovedness. Each person Jesus touched knew, perhaps for the first time, that their life mattered; that they were loved and cherished."

I cannot believe that he would have been able to do this, had he not experienced this kind of love for himself, growing up. So I think that the most we can do for anyone we care for is what Mary did for her son, to love and cherish them, so that they know they are beloved. So that they in their turn can go on to love others, as Jesus did. As we do, the best that we can.

Friday, 9 August 2024

Tempering Our Passions

The other day, I was talking with a friend, and she mentioned that she was planning to begin a doctorate in a couple of years' time, about the life of a little known person whom she'd become fascinated by. While she was speaking about it, her whole body became animated: her eyes lit up, her voice grew warmer, and it was easy to tell how passionate she felt about sharing this man's story with the wider world.

And I noticed my own reaction: I was delighted that she'd found something she felt so strongly about, yet relieved that it wouldn't be my job to put in all those years of effort. Which surprised me. A few years ago, my reaction would have been quite different. I would have been thinking, "Oh, wow! I wanna do a doctorate too!" Instead of, "Meh. Sounds like too much hard work to me." This passion was hers, not mine.

My dictionary defines passion as "a very strong feeling", whether it is an emotion, e.g. love, hate, anger, enthusiasm; or of liking something e.g. a hobby or activity; or of sexual love; of a "state of being very angry". Whichever definition you go with, passion is a Very Strong Feeling.

On the positive side, our passions can motivate us, enthuse us, keep a bright flame of desire burning in our hearts and minds, as we labour to achieve a particular goal. Which is marvellous, if that goal is a positive one, like my friend's, to share an important true story with the world. In which case, we can safely give our passions free rein and follow where they lead.

The danger can come when the passion is ignited by words of hatred, words of fear. When we are swept up by another's originating emotions and find ourselves acting irrationally, hatefully, harming others, inflamed by falsehoods and lies. Or when we find ourselves losing our temper or being impatient with someone else, because they hav annoyed us or don't agree with us or dare to oppose us.

As has been happening only too frequently in the past week or so, when the Far Right has inflamed people's passions, inciting riots and acts of vandalism and violence.

So we need to learn to temper our passions. "Temper" in this context means to "act as a neutralizing or counterbalancing force to something. e.g. 'their idealism is tempered with realism'" In much the same way as a blacksmith tempers steel by reheating and then cooling it.

Friday, 2 August 2024

Nurturing Stability

Benedictine monks and nuns take a vow of stability, as the website of Mount Michael Abbey in Elkhorn, Nebraska explains: "Benedictine monks vow stability to the community in which they choose to live. This vow helps the monk persevere in the search for God. The promise is that the monk will stay with the other members of the community for mutual support in searching. While an individual monk may at times become discouraged in his search for God, the vow of stability helps him to see that others are searching as well and have a sense of the proper direction for that search."

Friday, 26 July 2024

A Challenge for Us All

The Black American Marxist and feminist political activist, philosopher, academic and author, Angela Davis, once wrote, "You have to act as if it were possible to radically transform the world. and you have to do it all the time."

Friday, 19 July 2024

Effective Anger

The Ancient Greek philosopher, Aristotle, once wrote, "Anyone can get angry, that is easy. But to be angry with the right person, in the right measure, at the right time, for the right purpose, and in the right way, that is hard."